Dir.: Kelly Reichardt

Plot: A band of 19th century pioneers led astray by a manipulative charlatan start to unravel in hostile terrain.

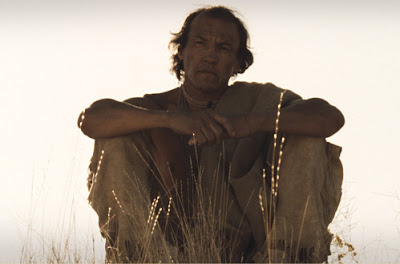

Described helpfully in the accompanying leaflet as an ‘indie Western’, cult filmmaker Kelly Reichardt’s latest offering is a bleak, bleached-out odyssey following a cluster of lost would-be pioneers in 1840s Oregon plodding hopelessly through untamed territory. Tempted off the main trail by Stephen Meek, a colourful frontiersman with promises of a shortcut, the three couples come to bitterly regret their decision, their spirits ebbing away in conjunction with their supplies. Distrustful of their guide and of an Indian captive they cannot decide whether or not to kill, their fragile hopes start to crumble into an existential dread.

Meek’s Cutoff is a lean, terse, grimy look at history which feels intensely real in a way that is astonishingly rare in period films. Much of this is due to Michelle Williams' performance as Emily, a heartbreakingly stoic exterior just about hiding her profound awareness of the convoy’s probable doom and her tight-lipped rage at Meek’s empty promises. Because although the whole cast (including The Wire’s Neal Huff and There Will Be Blood’s Paul Dano) acquit themselves admirably, the film is really about the women of the caravan and their grindingly hard, silent lives. Reichardt really taps into this feeling, often grouping the men together muttering out of earshot, whilst the women observe wordlessly from the sidelines. When Meek calls for a vote on the fate of their Indian prisoner, there is never any question of the women lifting their hands.

The other remarkable element which makes the film stand out is the way Kelly Reichhardt shoots in an almost documentary style, alternating between long shots which neutrally observe the pioneers unconsciously going about their routine, and intimate close-ups grasping the details of the work. Many of the scenes simply show everyday tasks, which you will find either transportingly hypnotic or incredibly tedious, depending on your interest in history. There is no convenient cinematic tweaking placed between the story and the audiencee: the night scenes are actually almost pitch black, the day scenes are eyeball-scorchingly bright, the dialogue is occasionally indistinguishable. Reichardt approaches her subject matter like an anthropologist recording a lost tribe, and the result is a representation of pioneer life which is almost spookily convincing.

The ending of the film is shamelessly obscure in a way reminiscent of last year’s A Serious Man, and now as then the audience reaction in the cinema was mild annoyance at the indie cult of anti-satisfaction. Personally, I'm going to word this carefully: I think the ambiguity of the ending worked here, but if this sort of thing starts becoming the norm, it will get annoying real fast.

|

| As inscrutable as the Indian who entrains it. |

Cries of ‘pretentious!’ have been levelled at the film, and specifically its ending, but while Meek’s Cutoff’s glacial pace and remote approach to storytelling might not be everyone’s cup of tea, pretentious it is not. It’s a very simple story about ordinary people, told in a remarkably straightforward fashion. Whereas a good indicator of a pretentious film is the director’s unmistakable presence in every meticulous, overwrought frame, Reichardt seems to try her utmost in Meek’s Cutoff to make the trappings of cinema invisible. The refreshing simplicity of her direction, reflecting her plain protagonists and their sparse landscape makes its skill and beauty almost seem coincidental. Similarly, whatever symbolism or subtext you choose to see (or not see) in the film is up to you – there is no feeling of the director hovering over you and cramming clunky allegories down your throat until you understand that THIS IS A METAPHOR FOR THE IRAQ WAR/RACISM/THE DEFENESTRATION OF PRAGUE. Ultimately, that’s where the film succeeds – it manages to provoke a great deal of thought without actually doing very much. Cinematic economy at its purest.

8/10

No comments:

Post a Comment